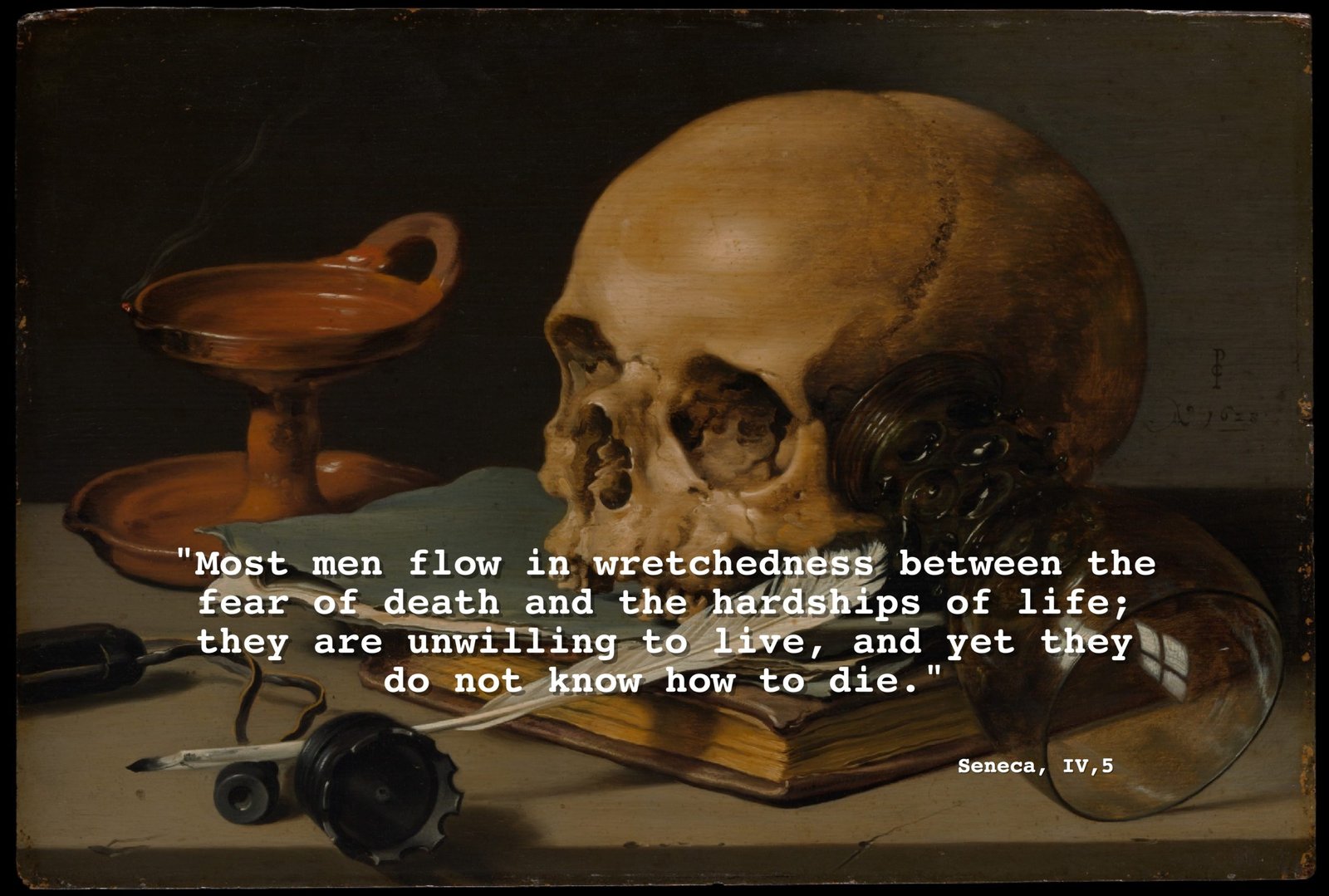

The fourth letter to Lucilius by Seneca teaches how to develop mental calm and reject the fear of death. Seneca begins by comparing a man who becomes wise with a boy who comes of age. And one of the things that age and wisdom bring is a more proper understanding of death:

“No evil is great which is the last evil of all. Death arrives; it would be a thing to dread, if it could remain with you. But death must either not come at all, or else must come and pass away.” (IV.3)

He says it is equally foolish to despise life and fear death, and tranquility can be achieved by learning that there is no reason to fear death, which is always with us. Seneca´s philosophy bears strong resemblances to Epicurus’ take on the subject: “Death, therefore, the most awful of evils, is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not.” as put in the Letter to Menoeceus.

Seneca then talks about a related issue, the quality of one’s life:

“No man can have a peaceful life who thinks too much about lengthening it … Most men ebb and flow in wretchedness between the fear of death and the hardships of life; they are unwilling to live, and yet they do not know how to die.” (IV.4 & IV.5).

In sequence, Seneca warns Lucilius not to trust Fortune, thereby implicitly advising him to make the best of every moment he’s got:

“No man has ever been so far advanced by Fortune that she did not threaten him as greatly as she had previously indulged him. Do not trust her seeming calm; in a moment the sea is moved to its depths. The very day the ships have made a brave show in the games, they are engulfed.” (IV.7)

Points:

- Do not fear death

- Focus on the quality of your life.

- Do not trust Fortune.

— — —

IV. On the Terrors of Death

1. Keep on as you have begun, and make all possible haste, so that you may have longer enjoyment of an improved mind, one that is at peace with itself. Doubtless you will derive enjoyment during the time when you are improving your mind and setting it at peace with itself; but quite different is the pleasure which comes from contemplation when one’s mind is so cleansed from every stain that it shines.

2. You remember, of course, what joy you felt when you laid aside the garments of boyhood and donned the man’s toga, and were escorted to the forum; nevertheless, you may look for a still greater joy when you have laid aside the mind of boyhood and when wisdom has enrolled you among men. For it is not boyhood that still stays with us, but something worse, — boyishness. And this condition is all the more serious because we possess the authority of old age, together with the follies of boyhood, yea, even the follies of infancy. Boys fear trifles, children fear shadows, we fear both.

3. All you need to do is to advance; you will thus understand that some things are less to be dreaded, precisely because they inspire us with great fear. No evil is great which is the last evil of all. Death arrives; it would be a thing to dread, if it could remain with you. But death must either not come at all, or else must come and pass away.

4. “It is difficult, however,” you say, “to bring the mind to a point where it can scorn life.” But do you not see what trifling reasons impel men to scorn life? One hangs himself before the door of his mistress; another hurls himself from the house-top that he may no longer be compelled to bear the taunts of a bad-tempered master; a third, to be saved from arrest after running away, drives a sword into his vitals. Do you not suppose that virtue will be as efficacious as excessive fear? No man can have a peaceful life who thinks too much about lengthening it, or believes that living through many consulships is a great blessing.

5. Rehearse this thought every day, that you may be able to depart from life contentedly; for many men clutch and cling to life, even as those who are carried down a rushing stream clutch and cling to briars and sharp rocks. Most men ebb and flow in wretchedness between the fear of death and the hardships of life; they are unwilling to live, and yet they do not know how to die.

6. For this reason, make life as a whole agreeable to yourself by banishing all worry about it. No good thing renders its possessor happy, unless his mind is reconciled to the possibility of loss; nothing, however, is lost with less discomfort than that which, when lost, cannot be missed. Therefore, encourage and toughen your spirit against the mishaps that afflict even the most powerful.

7. For example, the fate of Pompey was settled by a boy and a eunuch, that of Crassus by a cruel and insolent Parthian. Gaius Caesar ordered Lepidus to bare his neck for the axe of the tribune Dexter; and he himself offered his own throat to Chaerea.[1] No man has ever been so far advanced by Fortune that she did not threaten him as greatly as she had previously indulged him. Do not trust her seeming calm; in a moment the sea is moved to its depths. The very day the ships have made a brave show in the games, they are engulfed.

8. Reflect that a highwayman or an enemy may cut your throat; and, though he is not your master, every slave wields the power of life and death over you. Therefore I declare to you: he is lord of your life that scorns his own. Think of those who have perished through plots in their own homes, slain either openly or by guile; you will then understand that just as many have been killed by angry slaves as by angry kings. What matter, therefore, how powerful he be whom you fear, when every one possesses the power which inspires your fear?

9. “But,” you will say, “if you should chance to fall into the hands of the enemy, the conqueror will command that you be led away,” — yes, whither you are already being led.[2] Why do you voluntarily deceive yourself and require to be told now for the first time what fate it is that you have long been labouring under? Take my word for it: since the day you were born you are being led thither. We must ponder this thought, and thoughts of the like nature, if we desire to be calm as we await that last hour, the fear of which makes all previous hours uneasy.

10. But I must end my letter. Let me share with you the saying which pleased me to-day. It, too, is culled from another man’s Garden:[3] “Poverty brought into conformity with the law of nature, is great wealth.” Do you know what limits that law of nature ordains for us? Merely to avert hunger, thirst, and cold. In order to banish hunger and thirst, it is not necessary for you to pay court at the doors of the purse-proud, or to submit to the stern frown, or to the kindness that humiliates; nor is it necessary for you to scour the seas, or go campaigning; nature’s needs are easily provided and ready to hand.

11. It is the superfluous things for which men sweat, — the superfluous things that wear our togas threadbare, that force us to grow old in camp, that dash us upon foreign shores. That which is enough is ready to our hands. He who has made a fair pact with poverty is rich.

Farewell.

Footnotes

- ↑ A reference to the murder of Caligula, on the Palatine, A.D. 41.

- ↑ i.e., to death.

- ↑ The Garden of Epicurus. Frag. 477 and 200 Usener.

- image: Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill from Pieter Claesz

One Reply to “Letter IV. On the Terrors of Death”