In letter 47 Seneca talks about the relationship between master and slave and brings some of his most striking phrases: “No servitude is more disgraceful than that which is self-imposed. ” (XLVII, 17)

The letter is long, but a very interesting read, mainly because of the details of Roman life narrated by Seneca ranging from gastronomic and sexual orgies to the trade, liberation and capture of slaves. Seneca reminds us that Plato and Diogenes as well as Hecuba (queen of Troy) fell into captivity and became slaves.

The crux of the letter, valid even today is : “Treat your inferiors as you would be treated by your betters” (XLVII, 11) and teaches us to treat people “I propose to value men according to their character, and not according to their duties. Each man acquires his character for himself, but accident assigns his duties.” (XLVII, 15)

Seneca concludes the letter by stating that all men have the same divine origin and that we are all slaves to something:

“He is a slave.” His soul, however, may be that of a freeman. “He is a slave.” But shall that stand in his way? Show me a man who is not a slave; one is a slave to lust, another to greed, another to ambition, and all men are slaves to fear. I will name you an ex-consul who is slave to an old hag, a millionaire who is slave to a serving-maid; I will show you youths of the noblest birth in serfdom to pantomime players! No servitude is more disgraceful than that which is self-imposed. (XLVII, 17)

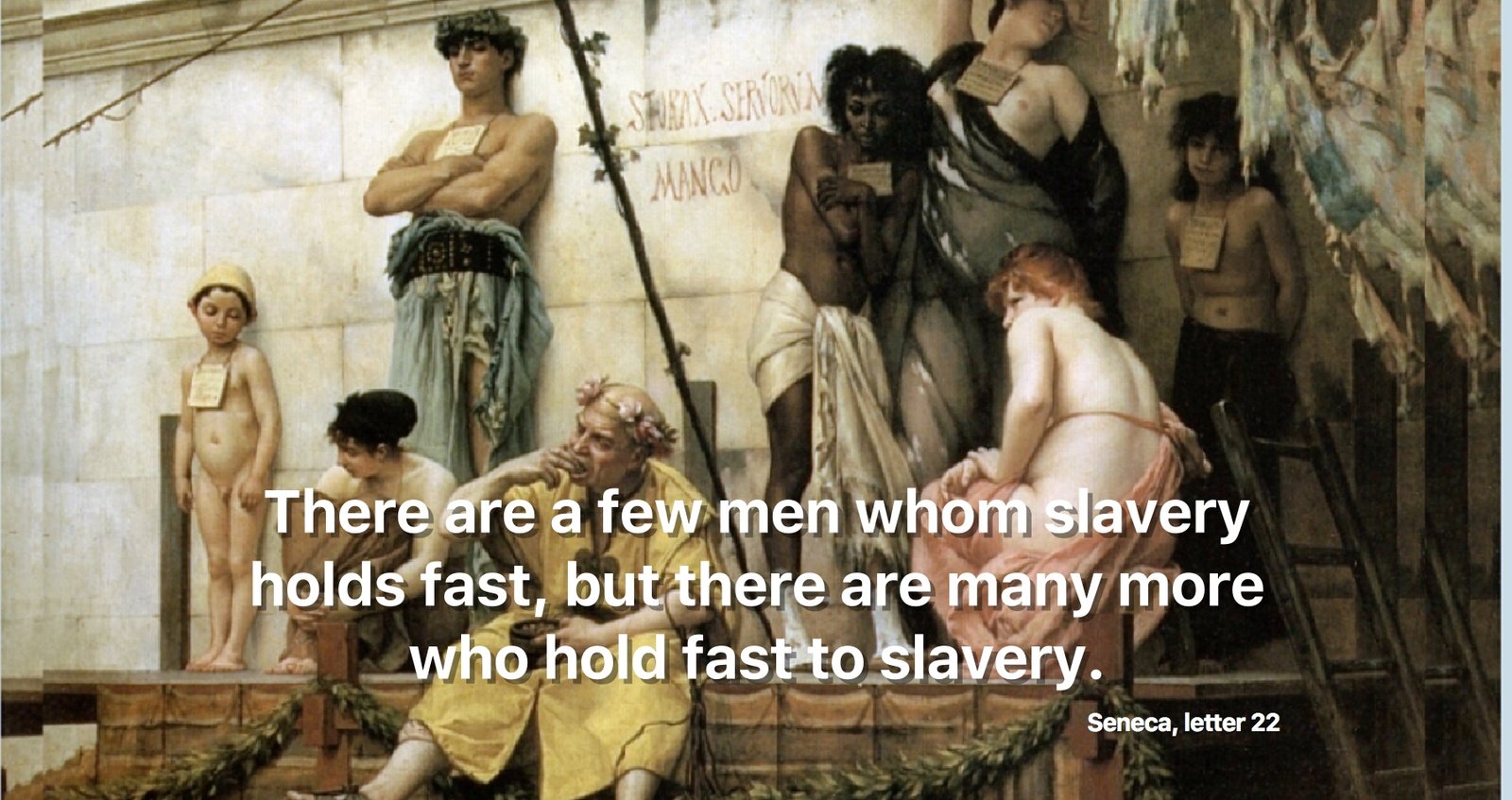

(image: Gustave Boulanger The Slave Market)

XLVII. On Master and Slave

1. I am glad to learn, through those who come from you, that you live on friendly terms with your slaves. This befits a sensible and well-educated man like yourself. “They are slaves,” people declare.[1] Nay, rather they are men. “Slaves!” No, comrades. “Slaves!” No, they are unpretentious friends. “Slaves!” No, they are our fellow-slaves, if one reflects that Fortune has equal rights over slaves and free men alike.

2. That is why I smile at those who think it degrading for a man to dine with his slave. But why should they think it degrading? It is only because purse-proud etiquette surrounds a householder at his dinner with a mob of standing slaves. The master eats more than he can hold, and with monstrous greed loads his belly until it is stretched and at length ceases to do the work of a belly; so that he is at greater pains to discharge all the food than he was to stuff it down.

3. All this time the poor slaves may not move their lips, even to speak. The slightest murmur is repressed by the rod; even a chance sound, – a cough, a sneeze, or a hiccup, – is visited with the lash. There is a grievous penalty for the slightest breach of silence. All night long they must stand about, hungry and dumb.

4. The result of it all is that these slaves, who may not talk in their master’s presence, talk about their master. But the slaves of former days, who were permitted to converse not only in their master’s presence, but actually with him, whose mouths were not stitched up tight, were ready to bare their necks for their master, to bring upon their own heads any danger that threatened him; they spoke at the feast, but kept silence during torture.

5. Finally, the saying, in allusion to this same high-handed treatment, becomes current: “As many enemies as you have slaves.” They are not enemies when we acquire them; we make them enemies. I shall pass over other cruel and inhuman conduct towards them; for we maltreat them, not as if they were men, but as if they were beasts of burden. When we recline at a banquet, one slave mops up the disgorged food, another crouches beneath the table and gathers up the left-overs of the tipsy guests.

6. Another carves the priceless game birds; with unerring strokes and skilled hand he cuts choice morsels along the breast or the rump. Hapless fellow, to live only for the purpose of cutting fat capons correctly, – unless, indeed, the other man is still more unhappy than he, who teaches this art for pleasure’s sake, rather than he who learns it because he must.

7. Another, who serves the wine, must dress like a woman and wrestle with his advancing years; he cannot get away from his boyhood; he is dragged back to it; and though he has already acquired a soldier’s figure, he is kept beardless by having his hair smoothed away or plucked out by the roots, and he must remain awake throughout the night, dividing his time between his master’s drunkenness and his lust; in the chamber he must be a man, at the feast a boy.[2]

8. Another, whose duty it is to put a valuation on the guests, must stick to his task, poor fellow, and watch to see whose flattery and whose immodesty, whether of appetite or of language, is to get them an invitation for to-morrow. Think also of the poor purveyors of food, who note their masters’ tastes with delicate skill, who know what special flavours will sharpen their appetite, what will please their eyes, what new combinations will rouse their cloyed stomachs, what food will excite their loathing through sheer satiety, and what will stir them to hunger on that particular day. With slaves like these the master cannot bear to dine; he would think it beneath his dignity to associate with his slave at the same table! Heaven forfend! But how many masters is he creating in these very men!

9. I have seen standing in the line, before the door of Callistus, the former master,[3]of Callistus; I have seen the master himself shut out while others were welcomed, – the master who once fastened the “For Sale” ticket on Callistus and put him in the market along with the good-for-nothing slaves. But he has been paid off by that slave who was shuffled into the first lot of those on whom the crier practises his lungs; the slave, too, in his turn has cut his name from the list and in his turn has adjudged him unfit to enter his house. The master sold Callistus, but how much has Callistus made his master pay for!

10. Kindly remember that he whom you call your slave sprang from the same stock, is smiled upon by the same skies, and on equal terms with yourself breathes, lives, and dies. It is just as possible for you to see in him a free-born man as for him to see in you a slave. As a result of the massacres in Marius’s[4] day, many a man of distinguished birth, who was taking the first steps toward senatorial rank by service in the army, was humbled by fortune, one becoming a shepherd, another a caretaker of a country cottage. Despise, then, if you dare, those to whose estate you may at any time descend, even when you are despising them.

11. I do not wish to involve myself in too large a question, and to discuss the treatment of slaves, towards whom we Romans are excessively haughty, cruel, and insulting. But this is the kernel of my advice: Treat your inferiors as you would be treated by your betters. And as often as you reflect how much power you have over a slave, remember that your master has just as much power over you.

12. “But I have no master,” you say. You are still young; perhaps you will have one. Do you not know at what age Hecuba entered captivity, or Croesus, or the mother of Darius, or Plato, or Diogenes?[5]

13. Associate with your slave on kindly, even on affable, terms; let him talk with you, plan with you, live with you. I know that at this point all the exquisites will cry out against me in a body; they will say: “There is nothing more debasing, more disgraceful, than this.” But these are the very persons whom I sometimes surprise kissing the hands of other men’s slaves.

14. Do you not see even this, – how our ancestors removed from masters everything invidious, and from slaves everything insulting? They called the master “father of the household,” and the slaves “members of the household,” a custom which still holds in the mime. They established a holiday on which masters and slaves should eat together, – not as the only day for this custom, but as obligatory on that day in any case. They allowed the slaves to attain honours in the household and to pronounce judgment;[6] they held that a household was a miniature commonwealth.

15. “Do you mean to say,” comes the retort, “that I must seat all my slaves at my own table?” No, not any more than that you should invite all free men to it. You are mistaken if you think that I would bar from my table certain slaves whose duties are more humble, as, for example, yonder muleteer or yonder herdsman; I propose to value them according to their character, and not according to their duties. Each man acquires his character for himself, but accident assigns his duties. Invite some to your table because they deserve the honour, and others that they may come to deserve it. For if there is any slavish quality in them as the result of their low associations, it will be shaken off by intercourse with men of gentler breeding.

16. You need not, my dear Lucilius, hunt for friends only in the forum or in the Senate-house; if you are careful and attentive, you will find them at home also. Good material often stands idle for want of an artist; make the experiment, and you will find it so. As he is a fool who, when purchasing a horse, does not consider the animal’s points, but merely his saddle and bridle; so he is doubly a fool who values a man from his clothes or from his rank, which indeed is only a robe that clothes us.

17. “He is a slave.” His soul, however, may be that of a freeman. “He is a slave.” But shall that stand in his way? Show me a man who is not a slave; one is a slave to lust, another to greed, another to ambition, and all men are slaves to fear. I will name you an ex-consul who is slave to an old hag, a millionaire who is slave to a serving-maid; I will show you youths of the noblest birth in serfdom to pantomime players! No servitude is more disgraceful than that which is self-imposed. You should therefore not be deterred by these finicky persons from showing yourself to your slaves as an affable person and not proudly superior to them; they ought to respect you rather than fear you.

18. Some may maintain that I am now offering the liberty-cap to slaves in general and toppling down lords from their high estate, because I bid slaves respect their masters instead of fearing them. They say: “This is what he plainly means: slaves are to pay respect as if they were clients or early-morning callers!” Anyone who holds this opinion forgets that what is enough for a god cannot be too little for a master. Respect means love, and love and fear cannot be mingled.

19. So I hold that you are entirely right in not wishing to be feared by your slaves, and in lashing them merely with the tongue; only dumb animals need the thong. That which annoys us does not necessarily injure us; but we are driven into wild rage by our luxurious lives, so that whatever does not answer our whims arouses our anger.

20. We don the temper of kings. For they, too, forgetful alike of their own strength and of other men’s weakness, grow white-hot with rage, as if they had received an injury, when they are entirely protected from danger of such injury by their exalted station. They are not unaware that this is true, but by finding fault they seize upon opportunities to do harm; they insist that they have received injuries, in order that they may inflict them.

21. I do not wish to delay you longer; for you need no exhortation. This, among other things, is a mark of good character: it forms its own judgments and abides by them; but badness is fickle and frequently changing, not for the better, but for something different.

Farewell

Footnotes

- ↑ Much of the following is quoted by Macrobius, Sat. i. 11. 7 ff., in the passage beginning vis tu cogitare eos, quos ios tuum vocas, isdem seminibus ortos eodem frui caelo, etc.

- ↑ Glabri, delicati, or exoleti were favourite slaves, kept artifically youthful by Romans of the more dissolute class. Cf. Catullus, lxi. 142, and Seneca, De Brevitate Vitae, 12. 5 (a passage closely resembling the description given above by Seneca), where the master prides himself upon the elegant appearance and graceful gestures of these favourites.

- ↑ The master of Callistus, before he became the favourite of Caligula, is unknown.

- ↑ There is some doubt whether we should not read Variana, as Lipsius suggests. This method of qualifying for senator suits the Empire better than the Republic. Variana would refer to the defeat of Varus in Germany, A.D. 9.

- ↑ Plato was about forty years old when he visited Sicily, whence he was afterwards deported by Dionysius the Elder. He was sold into slavery at Aegina and ransomed by a man from Cyrene. Diogenes, while travelling from Athens to Aegina, is said to have been captured by pirates and sold in Crete, where he was purchased by a certain Corinthian and given his freedom.

- ↑ i.e., as the praetor himself was normally accustomed to do.